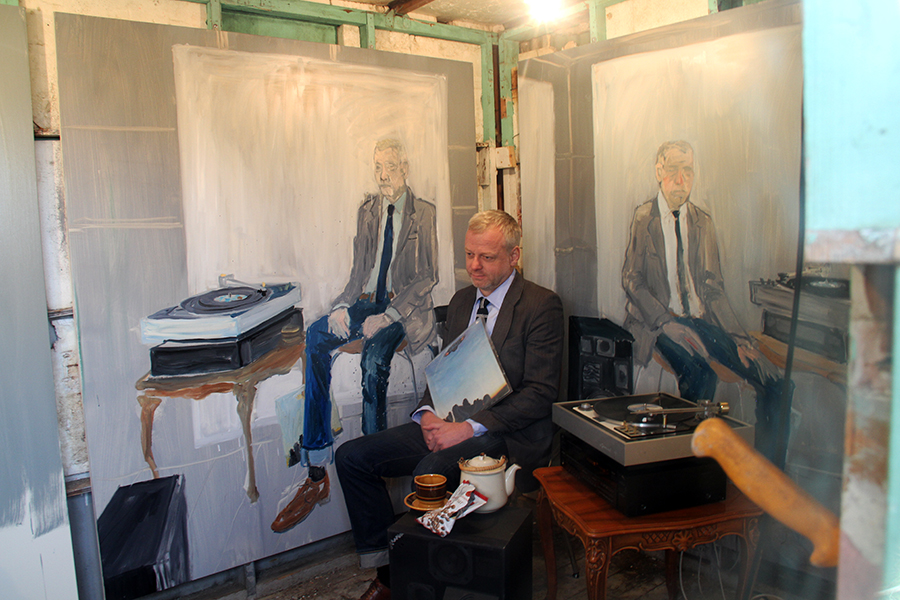

Ragnar Kjartansson – Bjarni Bömmer listens to Take it Easy by the Eagles.

Ragnar Kjartansson draws on the entire arc of art in his performative practice. The history of film, music, theatre, visual culture and literature find their way into his video installations, durational performances, drawing and painting. Pretending and staging become key tools in the artist’s attempt to convey sincere emotion and offer a genuine experience to the audience.

Kjartansson’s work has been exhibited widely. Recent solo exhibitions and performances have been held at the New Museum, ICA Boston, Guggenheim Bilbao, Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, the Carnegie Museum of Art, and PS1 MoMA. In 2011, he was the recipient of Performa’s 2011 Malcolm McLaren Award for his performance ‘Bliss’. In 2009, Kjartansson represented Iceland at the Venice Biennale, and in 2013 his work was featured at the Biennale’s main exhibition, The Encyclopedic Palace. Kjartansson was born in 1976 in Reykjavík and studied at the Iceland Academy of the Arts and The Royal Academy, Stockholm.

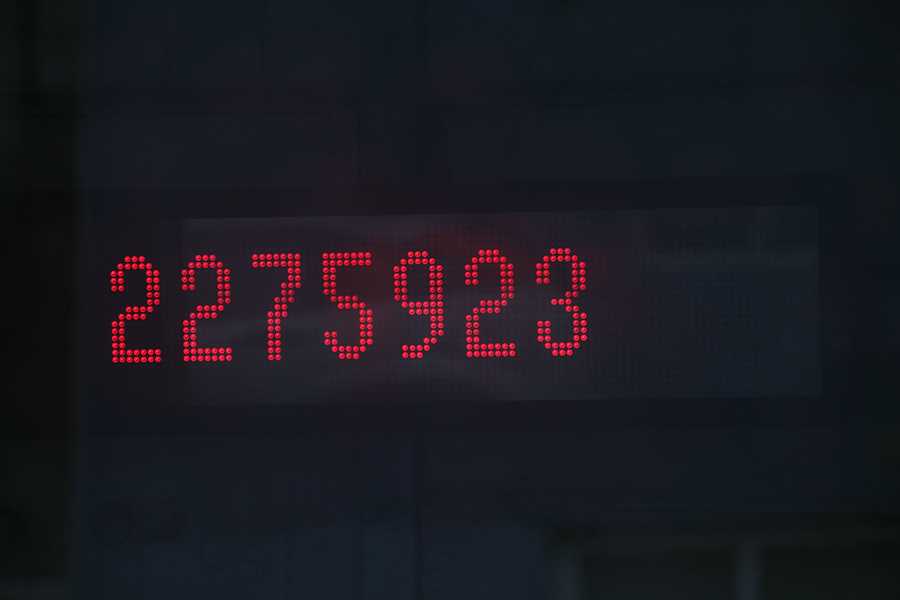

Kristján Guðmundsson – Exhibition Seconds

This work consists of a computer software showing the exact duration of the exhibition on a screen from the time it is opened on 4th of September at 20.00 until its over at 20.00 on the 4th of October 2014 – exactly 2,592,000 seconds. The countdown in seconds continues until the end of the exhibition when the screen shows the number zero. In this way time is structured and made tangible because it is contained in advance. The countdown brings us not to the beginning of an event, but to it´s finality.

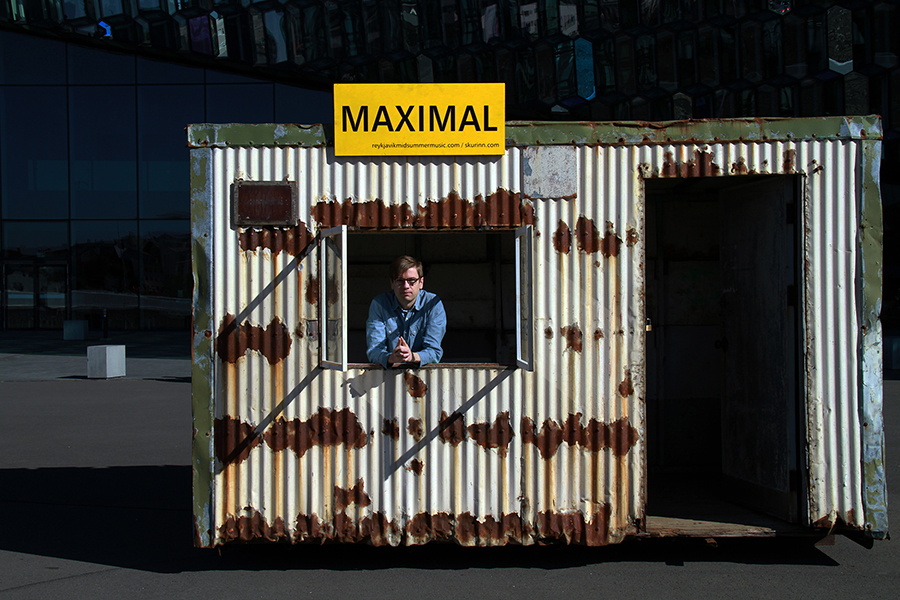

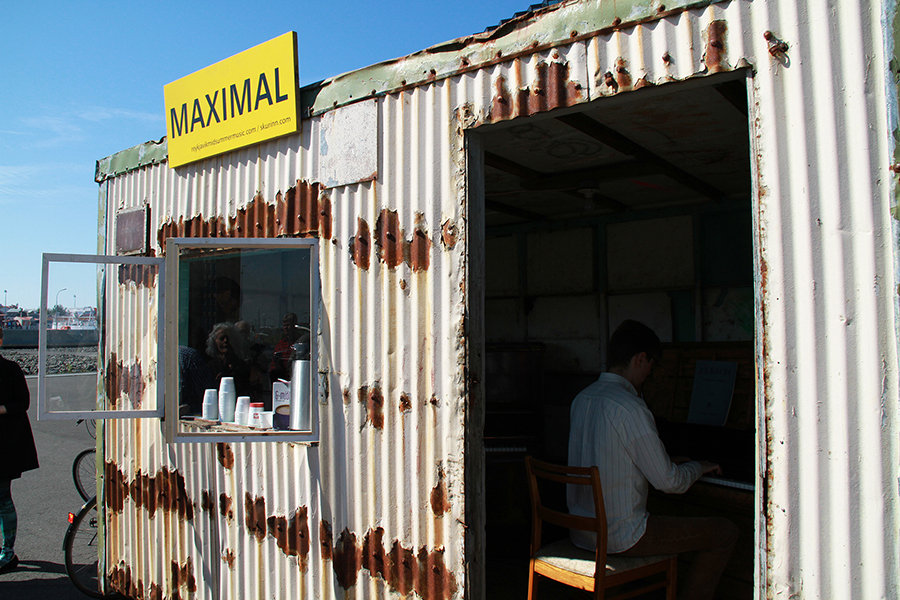

Vikingur Heiðar and The Midsummer Music

The Shed reflects the life of a musician, that rehearses for weeks in all sorts of conditions and practices on pianos of various sort. Víkingur Heiðar practicing in The Shed for the opening of the festival Reykjavík Midsummer Music.

Sara Björnsdóttir – Nono Lisa

This is a speculation and a feeling of an artist about the existence of artists like herself and the culture within Icelandic society. A small society that often seems unconscious of a larger context and other cultural perspectives:

A certain cultural level reflects the need for art and culture – for the soul and the internal to constrict and push a person out in search of beauty, purpose, and meaning – and the ability to perceive subtle nuances of the environment. Icelandic cultural life is rich and not impoverished because of Icelandic artists’ driven, unrelenting need for creation and the joy they take in creating. The creation of art is a spiritual pursuit that takes places in the artist’s subconscious mind. The artist proffers work, guided by a force or desire to which he or she is often oblivious, but that exerts a strong influence and offers hints that the artist trusts.

The work Nono Lisa is an original. An original that contains a reproduction. A reproduction that would not exist except for the birth of the original, the most famous artwork in the world put in a work shed–turned cultural center. In creating the work Nono Lisa, art envy and cultural reluctance were on the artist’s mind. Art envy can be compared to the Freudian notion of penis envy. It suggests that one feels oneself to be lacking something and realizes that one has neither innate artistic ability nor the capacity to achieve a connection with art and, as a result, turns against artists and art. This envy is an unconscious and aggressive urge. To wish to be an artist oneself but at the same time have the desire to exterminate other artists and art. Cultural reluctance is an ambiguous term. There are culturally reluctant people, and one can say that Icelandic society is in a state of cultural reluctance. It is also possible to suffer from cultural reluctance, to feel anguish as a result of the cultural level of the society.

Sara Björnsdóttir

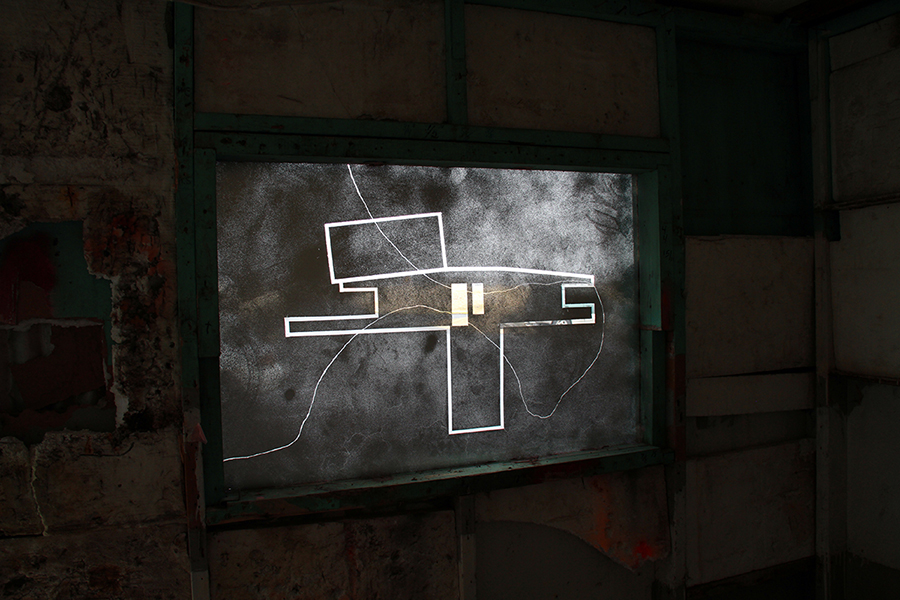

Sólveig Aðalsteinsdóttir – Randir

The Shed is located by the sea, at the start of a footpath that weaves its way along the outline of the peninsula. Just to the south along the path is another building, a concrete bunker from World War II. The path along the shoreline, along the horizon line of the sea, connects the two buildings and with them forms the linear work Randir (Lines).

drawing on shed: The Bunker

silver spray paint on glass

walk to the bunker along the horizon

drawing in bunker: The Shed

chalk pastel on concrete

Ólöf Nordal – Come ye, who wish to come.

“Come ye, who wish to come; go ye, who wish to go; stay ye, who wish to stay; me and mine remain unharmed” rings out from a closed shed in Lækjatorg. New Year’s Eve is the elves’ day of departure, and the custom is to leave the lights on in the house and the doors open for those who wish to enter. Hospitality has always been thought to be the greatest virtue and Icelanders have boasted of being a hospitable and open-minded nation, one that welcomes everyone. The work considers questions of open and closed, inside and out, belonging and exclusion.

Aslaug Thorlacius – Christmas at Látrar – A choir concert

In 1878 a new shepherd was appointed to the farm Látrar á Látraströnd, the nine-year-old Sæmundur Tryggvi Sæmundsson. As an adult, he recalls his first Christmas Eve at Látrar.

They began to sing all kinds of songs that people knew. Sæmundur remembers that they sang the following: Venus flies in flocks, A young maid walked in the woods, I walked in the woods where the road lay, If you want to help the world be happy and gay, Awake my soul rise up, The sun shone on the celestial throne, Wilted is the lily and wilted is the rose, I sat by the sea, Autumn is in the air, Hear the morning song at sea, What could be more joyous, O goddess of spring thou cometh, In the birch grove I rested, Ólafur rode along the cliffs, Home have I come with my head hanging low, Iceland of yore, I want a sweetheart oh so soon.

Drive in literature – FM 103,9

On December 18, 19, and 20 the Shed hosted a literary program from its temporary location in front of the Nordic House in Vatnsmýri. Conceived as a sort of drive-in, the audience could tune into FM 103.9 in their cars and hear a live broadcast from the Shed of authors reading from their books.

Overseeing the program was Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir.

mið. 18. des

Sjón – Mánasteinn

Birgitta Elín Hassell og Marta Hlín Magnadóttir – Gjöfin (Rökkurhæðir)

Hermann Stefánsson – Hælið

Sigurlín Bjarney Gísladóttir – Bjarg

Stefán Máni – Grimmd

fim. 19. des

Þorsteinn frá Hamri – Skessukatlar

Steinar Bragi – Reimleikar í Reykjavík

Gísli Sigurðsson– Leiftur á horfinni öld

Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir – Stúlka með maga

Þórdís Gísladóttir – Randalín og Mundi í Leynilundi

fös. 20. des

Yrsa Sigurðardóttir – Lygi

Sigurbjörg Þrastardóttir – Bréf frá borg dulbúinna storma

Þorsteinn Mar – Vargsöld

Sólveig Pálsdóttir – Hinir réttlátu

Eiríkur Guðmundsson – 1983

Dodda Maggý – ÆSA

The sound installation Æsa (2013) is a ten-part choral work composed especially for the Shed. The work, which occupies the vague terrain between music and sound art, can be described as a sort of conversation with the weather and the sea.

Húbert Nói – Consciuos

The darkroom of the mind.

Early in his carrier the exhibition space and its interior became one of Jóhannesson’s location of surveys. How the exterior develops and is stored in a human being, the location and navigation in that world, and then again the comparison to the outside. In this work the question forwarded is, does an exhibition space develop conscious with the collective memory of the ones attending?

Hrafnkell Sigurðsson – SMÍÐ

Am I somewhere?

Somehow, one gets the feeling of being – an individual and part of a whole, a community, a settlement, a nation. We reflect ourselves in the people around us as they reflect themselves in us; we become endless variations of the concept of ourselves, we act out our reflection, a reflection of a reflection. The Icelandic self-image is like glass, strong and fragile: it reveals success and braggadocio and dogged determination, and with it comes a faint smell of guano under the cologne, a brusque managerial “all right then” echoes under the techno beat, Icelandic happiness hinges on hard work, we connect our well-being to prosperity. But one can never be sure, never completely sure, never sure: Was I dreaming? Am I awake?Was I somewhere else? The foundation trembles under you: perhaps there is no palace, only a work shed, perhaps you’re just on break and not stationed in real life? Perhaps this is a lie, a fleeting dream, someone playing with us, was I somewhere, doing something?

Was I dreaming?

And then all of a sudden you’re haunted by this memory of forgotten pleasure, sure of having once experienced bliss and the wonderful incommunicable. You convince yourself that there is a place in the universe where all of this can be found. This is a place where you are at home and it is far and yet so close. Within us is a palace and one fine day all the lights there will be switched on again. Somewhere deep within us lives the memory of eternity.

Guðmundur Andri Thorsson

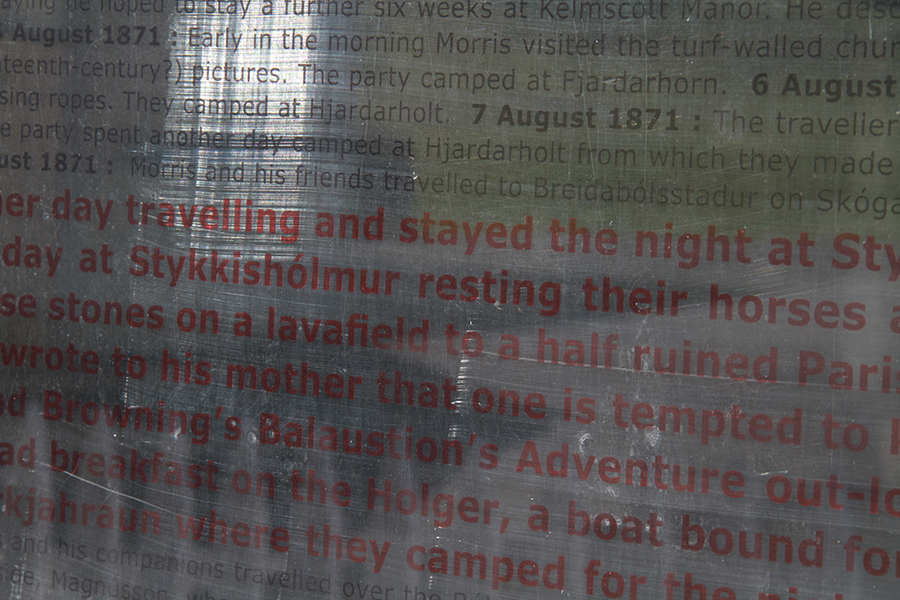

William and Jane – The Norwegian House in Stykkisholmur

While it’s safe to say that these buildings differ greatly both in size and appearance, they share the preservation of a collection of ideas, stories, transience, and inner as well as external beauty. Some might consider this weather-beaten and rusty shed to be incompatible with flowers and beauty suitable for a garden. Then there are others who have beauty in their backyards but will never notice it. This installation in the Shed is a kind of memorial to British philosopher, designer, romantic, and poet William Morris, who stayed in the Norwegian House August 10–12, 1871. The most interesting answers to life’s riddles are often found in unexpected contexts.

AlmaDís Kristinsdóttir, Director of the Norwegian House

Design March – Erling Jóhannesson

Throughout history and still today, people have wrestled with the aesthetics of form. Jewelry is more often than not evaluated on a purely aesthetic basis, and its purpose is first and foremost to embellish and adorn. But is it right to measure the beauty of an object solely on the basis of its texture and form? Our aesthetic judgment is also determined by subjective factors. Individual taste is shaped collectively with others and by the knowledge, education, or experience of the individual in question. This exhibition and collaboration with the Shed casts light on the connection between the aesthetics of form and the history of the nation.

Erling Jóhannesson, goldsmith

Form sem eru kunnugleg og vísa til reynslu okkar verða oft merkingarhlaðin og öðlast einskonar innri fegurð. Sú fegurð getur verið byggð á sameiginlegri reynslu okkar eða upplifun hvers og eins.

Form sem eru kunnugleg og vísa til reynslu okkar verða oft merkingarhlaðin og öðlast einskonar innri fegurð. Sú fegurð getur verið byggð á sameiginlegri reynslu okkar eða upplifun hvers og eins.

Með þessari sýningu og samstarfi við Menningarhúsið Skúrinn, er varpað ljósi á sambandið milli fagurfræði formsins og sögu þjóðar.

Árni Páll Jóhannesson – A Slower Speed of Light.

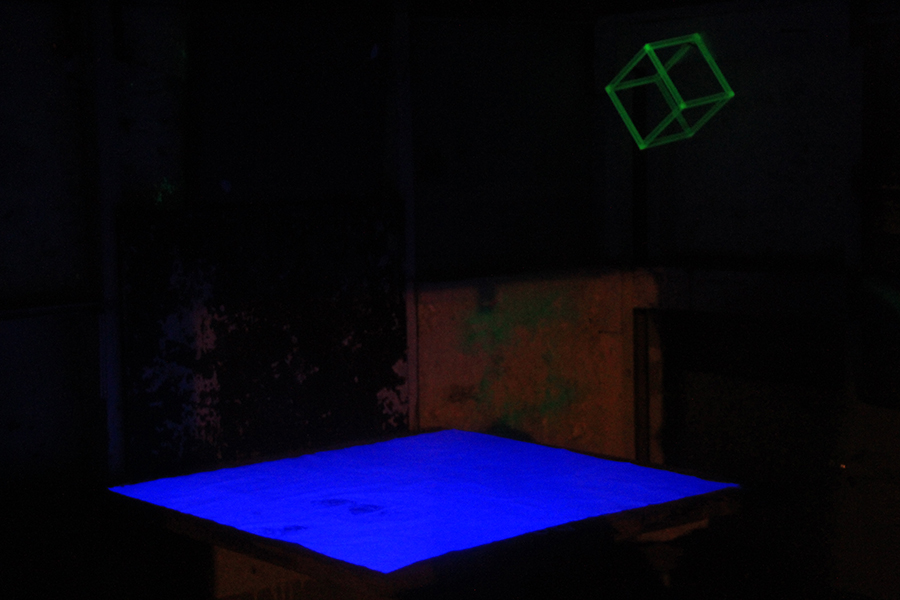

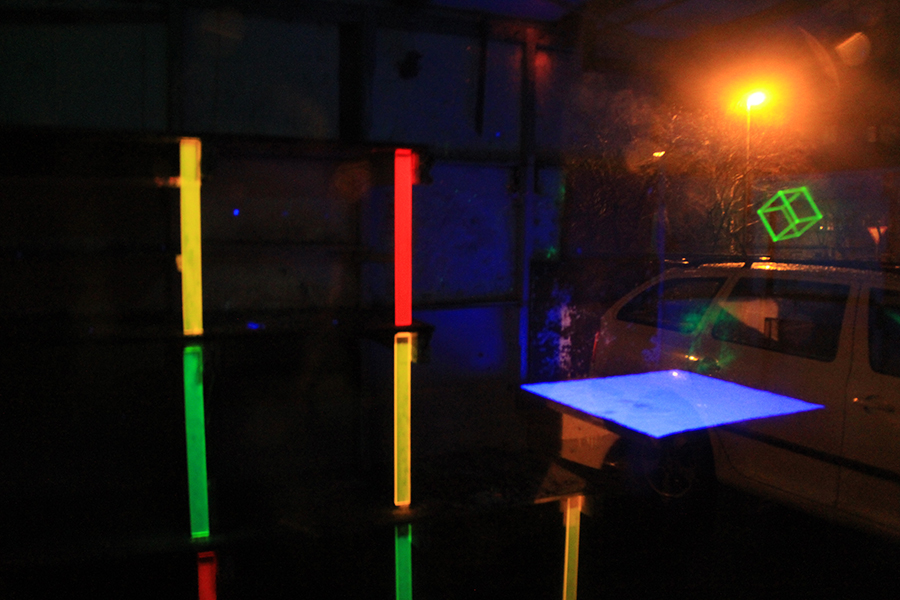

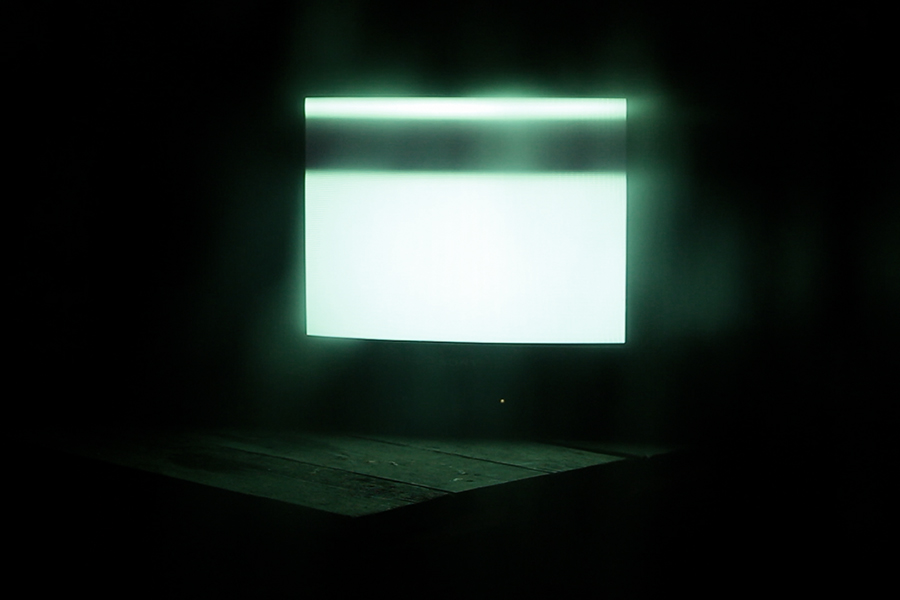

Sigurður Guðjónsson – Næturvarp

A new video work by Sigurður Guðjónsson entitled Næturvarp (Night Projection). A green light and horizontal black lines lit up the Shed, thus turning the exhibition space and the environment itself into material. Viewers could watch the projection through the Shed’s windows and hear the sound through the walls and glass.

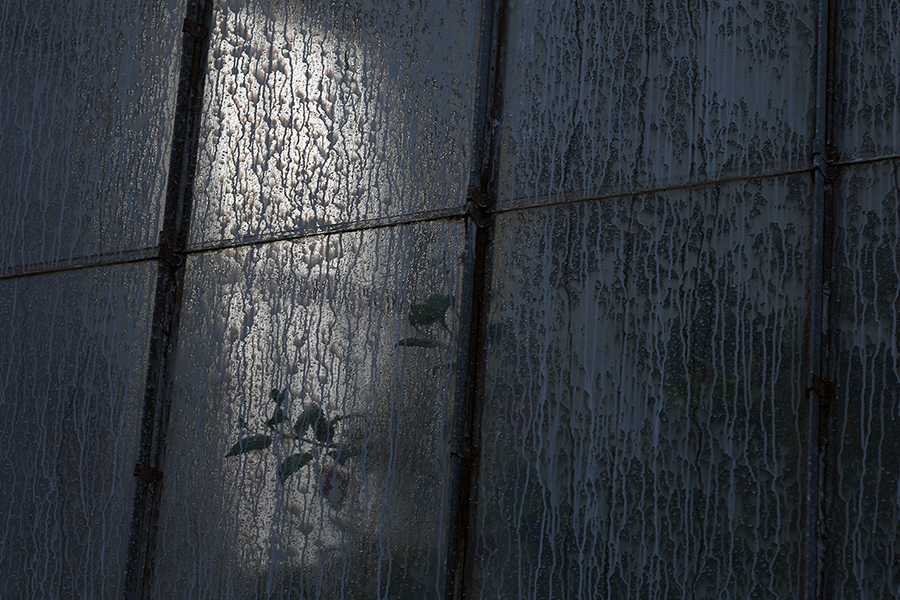

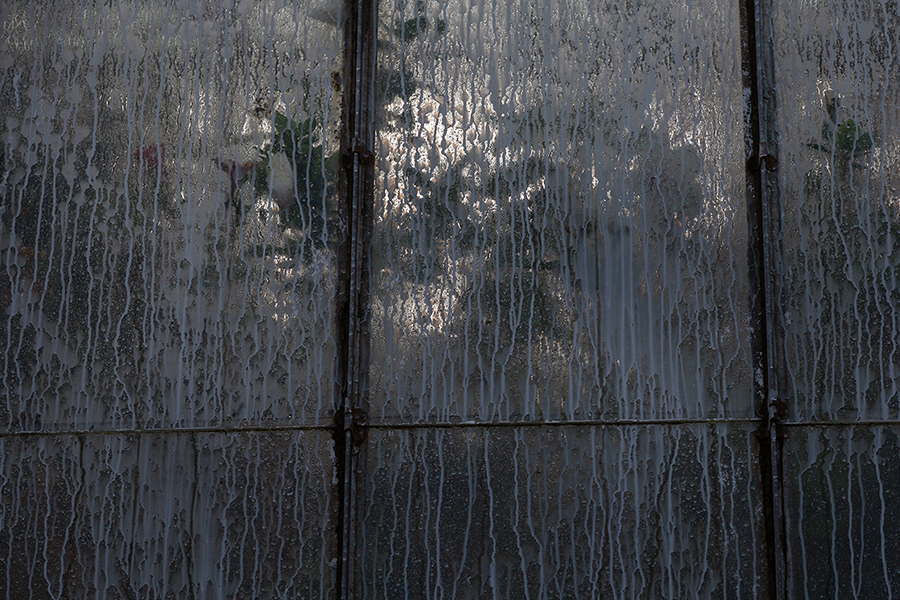

Katrín Elvarsdóttir – Here you´ll find no roses growing

http://katrinelvarsdottir.blogspot.com/2012/12/here-youll-find-no-roses-growing.html

The Shed was my inspiration for this work. This rusty, weather-beaten shed got me thinking about flowers – but the Shed is exactly the opposite of flowers and beauty. Could roses grow inside the Shed? What kind of roses? This installation is anattempt to guide the imagination concerning what kind of plants might grow there.

Katrín Elvarsdóttir

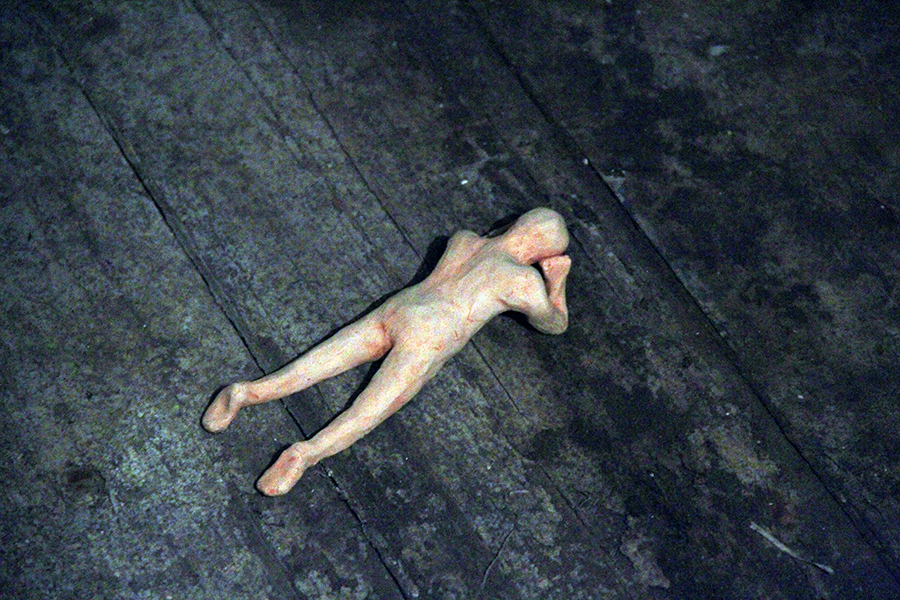

Guðjón Ketilsson – Melankólía

http://internet.is/gudjonket/gudjonket/HOME.html

I often think of those scenes in the Wim Wenders film Wings of Desire in which the protagonist, the angel, walks along the city streets and hears the thoughts of the people whom he passes by. One scene in particular was the spark that ignited my work for the Shed. In this scene the angel walks through the car of a train. We see the faces of the people sitting in silence in the train and at the same time hear short fragments of their thoughts as the angel walks by. All are deep in thought, immersed in their own worlds and the melancholy reflections on having a life. The melancholy that fills the space of the train in this film sequence is connected to the melancholy of the Shed, which my figures occupy.

Guðjón Ketilsson

The Opening Day – First Day of Summer 2012

The grand opening of the cultural center on the First Day of Summer. From inside the Shed a brass band could be heard playing.